-

|

|

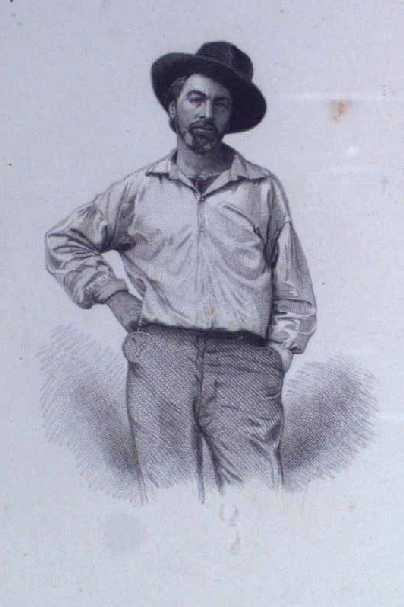

Chapter 4: American Transcendentalism

Walt Whitman

1819-1892

|

©

Paul P. Reuben

July 17, 2021

E-Mail

|

The Walt Whitman Association

"I was

simmering,

simmering, simmering; Emerson brought me to a boil." - WW

"Reminiscences of Walt Whitman," by John Townsend Trowbridge,

The

Atlantic Monthly,

February 1902

(The image above

and links

to E-Texts below:

Copyright Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price.

Reproduced with permission. For more information, visit

The

Walt Whitman Archive.)

|

Old

Walt

Old

Walt Whitman

Went finding and seeking,

Finding less than sought

Seeking more than found,

Every detail minding

Of the seeking or the finding.

Pleasured

equally

In seeking as in finding,

Each detail minding,

Old Walt went seeking

And finding.

Langston

Hughes, 1954

|

from A

Supermarket in California

Where

are we going Walt Whitman? The doors close in an

hour. Which way does your beard point tonight?

(I touch your book and dream of our odyssey in the

supermarket and feel absurd.)

Will we walk all night through solitary streets? The trees

add shade to shade, lights out in the houses, we'll both be

lonely.

Will we stroll dreaming of the lost America of love past

automobiles in driveways, home to our silent cottage?

Ah, dear father graybeard, lonely old courage-teacher, what

America did you have when Charon quit poling his ferry and

you got out on a smoking bank and stood watching the boat

disappear on the black waters of Lethe?

Allen

Ginsberg, 1956

|

|

Emerson's Letter to Whitman

21 July

Concord Masstts. 1855

Dear

Sir,

I am

not blind to the worth of the wonderful gift of "Leaves of Grass." I

find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has

yet contributed. I am very happy in reading it, as great power makes us

happy. It meets the demand I am always making of what seemed the

sterile & stingy nature, as if too much handiwork or too much lymph

in the temperament were making our western wits fat and mean. I give

you joy of your free brave thought. I have great joy in it. I find

incomparable things said incomparably well, as they must be. I find the

courage of treatment, which so delights us, & which large

perception only can inspire. I greet you at the beginning of a great

career, which yet must have had a long foreground somewhere for such a

start. I rubbed my eyes a little to see if this sunbeam were no

illusion; but the solid sense of the book is a sober certainty. It has

the best merits, namely of fortifying & encouraging. I did not know

until I, last night, saw the book advertised in a newspaper, that I

could trust the name as real and available for a post-office. I wish to

see my benefactor, & have felt much like striking my tasks, &

visiting New York to pay you my respects.

R. W.

Emerson

Mr.

Walter Whitman.

(from

the Norton Anthology of American Literature, Shorter Fourth

Edition, 546-547)

|

Top

Primary Works

Leaves of Grass

-

publication chronology

1855 July

published by Fowler & Wells, NY

1856 Second

Edition published by Fowler & Wells, NY

1860 Third Edition

published by Thayer and Eldridge, Boston

1867 Fourth

Edition published by William Chapin, NY

1868 Second Issue

of the Fourth Edition (contains Drum-Taps and Sequel including

"When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd")

1871 Fifth Edition

published by J. S. Redfield, NY

1876 Sixth Edition

published by WW in Camden

1881 Seventh

Edition, published by James R. Osgood & Co., Boston

1882 Eighth

Edition, published by David McKay, Philadelphia (includes Specimen

Days)

1892 Ninth Edition

published by David McKay, Philadelphia

Democratic

Vistas: The

Original Edition in Facsimile. Folsom, Ed (ed. and introd.).

Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2010.

Contributions

of Whitman

Richard Chase (in Walt

Whitman Reconsidered, 1955) discusses the following contributions

of the author and his book:

1. First

poetic writing which combines lyric verse and prose fiction - modern

poetry thrives on this combination.

2. Whitman made

the city and urban living conditions suitable settings for poetry.

3. In his

remarkable use of sex and sexual imagery, Whitman broke new ground in

American writing.

4. The central

metaphor, the unity of self with all other selves, is unique in

American literature.

Top

Leaves Of Grass (1855)

From its first

publication

in 1855, Whitman continued to add and expand the Leaves of Grass. He

published nine books with this same title - the last one appeared in

1892, the year of his death. His poems capture the sweeping expanse

of America. Among the numerous themes, Whitman discussed the unity of

I and you; good and evil; sex; death, the divine average, and

democracy.

Whitman on Leaves

Of

Grass:

1.

"Remember, the book arose out of my life in Brooklyn and NY from 1838

to 1853, absorbing a million people for 15 years, with an intimacy, an

eagerness, an abandon, probably never equalled."

2. "I saw, from

the time my enterprise and questionings positively shaped themselves

(how best can I express my own distinctive era and surroundings,

America, Democracy?), that the trunk and center whence the answer was

to radiate, and which all should return from straying, however far a

distance, must be identical body and soul, a personality, after many

considerations and pondering, I deliberately settled should be myself -

indeed could not be any other."

3. "An attempt of

a naive, masculine, affectionate, contemplative, sensual, imperious

person to cast into literature not only his grit and arrogance, but his

own flesh and form, undraped, regardless of models, regardless of

modesty or law; and ignorant as at first it appears, of all outside of

the fiercely loved land of his birth. ... The effects he produces in

his poems are no effects of artists or the arts, but the effects of the

original eye, or the actual atmosphere, or tree, or bird."

4. "Leaves of

Grass ... has mainly been . . . at attempt . . . to put 'a Person' a

human being (myself in the latter half of the nineteenth century, in

America) freely, fully, and truly on record. I could not find any

similar personal record in current literature that satisfied me."

Top

Selected Bibliography: Leaves of Grass

1980-Present

Adams, John. The

wound-dresser; Fearful symmetries [sound recording]. New

York: Elektra Nonesuch, p1989. Res / Compact Disc D ADAM-J WD

S82

Bradley, Sculley.

ed.

Leaves of grass: a textual variorum of the printed poems. New

York: New York UP, 1980. PS 3201

Greenspan, Ezra. ed.

Walt

Whitman's 'Song of Myself': A Sourcebook and Critical Edition.

NY: Routledge, 2005.

Grier, Edward F. ed.

Notebooks and unpublished prose manuscripts. 6 vols. New York:

New York UP, 1984. PS3202 .G75

Hindemith, Paul. When

lilacs last in the dooryard bloom'd [sound recording]: a

requiem for those we love. Cleveland, Ohio: Telarc, 1987. Res /

Compact Disc C HIND WLL D32

Orson Welles

reads Song

of myself [sound recording]. Guilford, CT: Audio-Forum,

1984. PS3222 .S6

Price, Kenneth M.,

and

Dennis Berthold. eds. Dear brother Walt: the letters of Thomas

Jefferson Whitman. Kent, Ohio: Kent State UP, 1984. PS3231

.A48

Sowder, Michael.

Whitman's Ecstatic Union: Conversion and Ideology in Leaves of

Grass. NY: Routledge, 2005.

Stacy, Jason. Walt

Whitman's Multitudes: Labor Reform and Persona in Whitman's

Journalism and the First Leaves of Grass, 1840-1855. NY: Peter

Lang, 2008.

Walt Whitman

[videorecording]. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Intellimation,

1988. Video Cassette PS305 .V65x 1988 no.12

Top

"The Song of Myself":

Its Structure:

I.

Paragraphs 1-18 the self; mystical interpretation of the self with all

life and experience.

II. Paragraphs

19-25 definition of the self; identification with the degraded and

transfiguration of it; final merit of self withheld; silence; end of

first half.

III. Paragraphs

26-38 life flowing in upon the self; evolutionary interpretation of

life.

IV. Paragraphs

39-41 the superman.

V. Paragraphs

42-52 larger questions of life - religions, faith, God, death;

immortality and happiness mystically affirmed

Its Meaning:

"Song of Myself" is

hardly

at all concerned with American nationalism, political democracy,

contemporary progress, or other social themes that are commonly

associated with Whitman's work. Its subject is a state of

illumination induced by two (or three) separate moments of ecstasy.

In more or less narrative sequence it describes those moments, their

sequels in life, and the doctrines to which they give rise. ... they

are presented dramatically, that is, as the new conviction of a hero,

and they are revealed by successive unfolding of his states of mind.

The hero - "I" - should not be confused with the Whitman of daily

life ... he is put forward as a representative workingman, but one

who prefers to loaf and invite his soul. Thus he is rough, sunburned,

bearded; he cocks his hat as he pleases, indoors or out ... his

really distinguishing feature is that he has been granted a vision,

as a result of which he has realized the potentialities latent in

every American and indeed, he says, in every living person. ... a

feeling seems to prevail that it has no structure properly speaking;

that it is inspired but uneven, repetitive, and especially weak in

its transitions from one theme to another. ... The true structure of

the poem is not primarily logical but psychological, and is not a

geometric figure but a musical progression. ... There is also a firm

narrative structure, one that becomes easier to grasp when we start

by dividing the poem into a number of parts or sequences.

First

Sequence (chants 1-4): the poet or hero introduced to his audience

- presents himself as a man who lives outdoors and worships his own

naked body, not the least part of which is vile. He is also in love

with his deeper self or soul. His joyful contentment can be shared by

you, the listener.

Second Sequence

(chant 5): the ecstasy. This consists in the rapt union of the poet and

his soul, and it is described figuratively, on the present occasion, in

terms of sexual union.

Third Sequence

(chant 6-19): the grass symbolizing the miracle of common things and

the divinity (which implies both the equality and the immortality) of

ordinary persons. The keynote of the sequence is the two words "I

observe."

Fourth Sequence

(chants 20-25): the poet in person. "Hankering, gross, mystical, nude",

he venerates himself as august and immortal, but so, he says, is

everyone else. The sequence ends with a dialogue between the poet and

his power of speech, during which the poet insists that his deeper self

- "the best I am" - is beyond expression.

Fifth Sequence

(chants 26-29): ecstasy through the senses. The poet decides to be

completely passive: "I think I will do nothing for a long time but

listen."

Sixth Sequence

(chants 30-38): the power of identification. After his first ecstasy,

the poet had acquired a sort of microscopic vision that enabled him to

find infinite wonders in the smallest and the most familiar things. The

second ecstasy (or a pair of them) has an entirely different effect,

conferring as it does a sort of vision that is both telescopic and

spiritual. ... "afoot with my vision" he ranges over the continent and

goes speeding through the heavens among tailed meteors. His secret is

the power of identification. Since everything emanates from the

universal soul, and since his own soul is of the same essence, he can

identify himself with every object and with every person living or

dead, heroic or criminal.

Seventh Sequence

(chants 39-41): the superman. When Hindu sages emerge from the state of

samadhi or absorption, they often have the feeling of being omnipotent.

It is so with the poet, who now feels gifted with superhuman powers. He

is the universally beloved Answerer (chant 39), the Healer, raising men

from their deathbeds (40), and then the Prophet (41) of a new religion

that outbids "the old cautious hucksters" by announcing that men are

divine and will eventually be gods.

Eighth Sequence

(chants 42-50): the sermon. He proclaims that society is full of

injustice, but the reality beneath it is deathless persons (42); that

he accepts and practices all religions, but looks beyond to "what is

untried and afterward (43); that he and his listeners are the fruit of

ages, and the seed of untold ages to be (44); that our final goal is

appointed: "God will be there and wait till we come" (45); that he

tramps a perpetual journey and longs for companions, to whom he will

reveal a new world by washing the gum from their eyes - but each must

then continue the journey alone (46); that he is the teacher of men who

work in the open air (47); that he is not curious about God, but sees

God everywhere, at every moment (48); that we shall all be reborn in

different forms ("No doubt I have died myself ten thousand times

before"); and that the evil in the world is like moonlight, a mere

reflection of the sun (49). The end of the sermon (50) is the hardest

passage to interpret in the whole poem. He seems to remember vague

shapes, and he beseeches these Outlines to let him reveal the "word

unsaid".

Ninth Sequence

(51-52): the poet's farewell. Having finished his sermon, the poet gets

ready to depart, that is to die and wait for another incarnation or

"fold of the future"' while still inviting others to follow. At the

beginning he had been leaning and loafing at ease in the summer grass.

Now, having rounded the circle, he bequeaths himself to the dirt "to

grow from the grass I love." I do not see how any careful reader,

unless blinded with preconceptions, could overlook the unity of the

poem in tone and image and direction.

(from

Malcolm Cowley, "Introduction to Leaves of Grass," 1959 in Walt

Whitman edited by Francis Murphy, 1969, Penguin Critical

Anthologies.)

Top

Selected Bibliography: Biographical

2000-Present

Blake, David H. Walt

Whitman and the Culture of American Celebrity. New Haven, CT:

Yale UP, 2006.

Epstein, Daniel M.

Lincoln and Whitman: Parallel Lives in Civil War Washington.

NY: Random House, 2005.

Folsom, Ed., and

Kenneth M.

Price. Re-Scripting Walt Whitman: An Introduction to His Life and

Work. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005.

Reynolds, David S. Walt

Whitman. NY: Oxford UP, 2004.

Roper, Robert. Now

the

Drum of War: Walt Whitman and His Brothers in the Civil War. NY:

Walker, 2008.

Thomas, M. Wynn.

Transatlantic Connections: Whitman U.S., Whitman U.K. Iowa

City: U of Iowa P, 2005.

Schmidgall, Gary.

ed.

Intimate with Walt: Selections from Whitman's Conversations with

Horace Traubel, 1888-1892. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2001.

Top

Selected Bibliography: Critical 2000-Present

Aspiz, Harold. So

Long!

Walt Whitman's Poetry of Death. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P,

2004.

Barrett, Faith. To

Fight

Aloud Is Very Brave: American Poetry and the Civil War. Amherst:

U of Massachusetts P, 2012.

Bellis, Peter J. Writing

Revolution: Aesthetics and Politics in Hawthorne, Whitman, and

Thoreau. Athens: U of Georgia P, 2003.

Blake, David H. Walt

Whitman and the Culture of American Celebrity. New Haven, CT:

Yale UP, 2006.

Bohan, Ruth L. Looking

into Walt Whitman: American Art, 1850-1920. University Park:

Pennsylvania State UP, 2006.

Corrigan, John. American

Metempsychosis: Emerson, Whitman, and the New Poetry. NY: Fordham

UP, 2012.

Davies, Catherine A.

Whitman's Queer Children: America's Homosexual Epics. NY:

Continuum, 2012.

Folsom, Ed. Whitman

Making Books, Books Making Whitman: A Catalog & Commentary.

Iowa City: University of Iowa, 2005.

Genoways, Ted. ed. Walt

Whitman: The Correspondence, VII. Iowa City: U of Iowa P,

2004.

- - -. Walt

Whitman and

the Civil War: America's Poet during the Lost Years of 1860-1862.

Berkeley: U of California P, 2009.

Grossman, Jay.

Reconstituting the American Renaissance: Emerson, Whitman, and the

Politics of Representation. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2003.

Hoffman, Tyler. American

Poetry in Performance: From Walt Whitman to Hip Hop. Ann Arbor: U

of Michigan P, 2011.

Hourihan, Paul. Mysticism

in American Literature: Thoreau's Quest and Whitman's Self.

Redding, CA: Vedantic Shores Press, 2004.

Katsaros, Laure Ann.

New

York-Paris: Whitman, Baudelaire, and the Hybrid City. Ann Arbor:

U of Michigan P, 2012.

Killingsworth, M.

Jimmie.

Walt Whitman and the Earth: A Study in Ecopoetics. Iowa City:

U of Iowa P, 2004.

Lawson, Andrew. Walt

Whitman and the Class Struggle. Iow City: U of Iowa P,

2006.

Mack, Stephen J. The

Pragmatic Whitman: Reimagining American Democracy. Iowa City: U

of Iowa P, 2002.

Maslan, Mark. Whitman

Possessed: Poetry, Sexuality, and Popular Authority. Baltimore:

Johns Hopkins UP, 2001.

Meehan, Sean R. Mediating

American Autobiography: Photography in Emerson, Thoreau, Douglass,

and Whitman. Columbia: U of Missouri P, 2008.

Miller, Matt. Collage

of

Myself: Walt Whitman and the Making of Leaves of Grass. Lincoln:

U of Nebraska P, 2010.

Moores, D. J. Mystical

Discourse in Wordsworth and Whitman: A Transatlantic Bridge.

Dudley, MA: Peeters, 2006.

Myerson, Joel. Supplement

to 'Walt Whitman: A Descriptive Bibliography.' Iowa City: U of

Iowa P, 2011.

Oliver, Charles M.

Critical Companion to Walt Whitman. NY: Facts on File, 2006.

Pannapacker,

William.

Revised Lives: Walt Whitman and Nineteenth-Century Authorship.

NY: Routledge, 2004.

Paryz, Marek. The

Postcolonial and Imperial Experience in American

Transcendentalism. NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Pollak, Vivian R. The

Erotic Whitman. Berkeley: U of California P, 2000.

Price, Kenneth M. To

Walt

Whitman, America. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P,

2004.

Robertson, Michael.

Worshipping Walt: The Whitman Disciples. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton UP, 2008.

Roper, Robert. Now

the

Drum of War: Walt Whitman and His Brothers in the Civil War. NY:

Walker, 2008.

Schmidgall, Gary.

ed.

Conserving Walt Whitman's Fame: Selections from Horace Traubel's

Conservator, 1890-1919. Iowa City: U of Iowa P, 2006.

Spengemann, William

C.

Three American Poets: Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and Herman

Melville. Notre Dame, IN: U of Notre Dame P, 2010.

Thomas, M. Wynn.

Transatlantic Connections: Whitman U.S., Whitman U.K. Iowa City: U of

Iowa P, 2005.

Vendler, Helen. Poets

Thinking: Pope, Whitman, Dickinson, Yeats. Cambridge: Harvard UP,

2004.

Whitley, Edward. American

Bards: Walt Whitman and Other Unlikely Candidates for National

Poet. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2010.

Williams, C. K. On

Whitman. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2010.

Top

Walt Whitman (1819-1892): A Brief Biography

A Student

Project by Jodie Quiñonez

The farm known as

West Hills

had been in the Whitman family for over a century before Walter

Whitman Sr. decided at the age of fifteen to leave the farm and

apprentice himself to carpentry in New York. He returned to the

country a "first-rate craftsman" (Bazalgette 19-21) and married

Louisa Van Velsor, a simple and illiterate woman, on June 8, 1816.

Soon after, Walter Whitman Jr., the second of four children was born

on May 31, 1819 at West Hills, Huntington Township, Long Island

(Bazalgette 23). The family soon began to distinguish him from his

father by simply calling him Walt. At the age of four Walt made the

first, of what was to become many, moves to Brooklyn. As a boy Walt

often explored the streets of his neighborhood and would take ferry

rides. On July 4, 1825, when Walt was only five years old, General

Lafayette visited Brooklyn. Lafayette had consented to stop on his

way through the city and lay the corner stone for the town's public

library. Lafayette picked up Walt, among the numerous children, and

held him momentarily before giving him a kiss and setting him back

down (Bazalgette 31). This was to become "one of the poet's most

cherished memories." (Allen xi)

At the age of five

Walt

began attending public school. Considered the son of a commoner, Walt

was only allowed to attend school in Brooklyn for six years. Walt,

however, would also go to Sunday school at St. Ann's. The education

that Walt received at St. Ann's would remain his "only foundation of

methodic and formal instruction" throughout his life (Bazalgette

31).

In 1830 Walt became

an

office boy in a law firm before moving on to work for a doctor. Soon

after, Walt began working in printing offices. It is here that Walt

began to learn the trade and became a printer's apprentice at the

Long Island Patriot. During the summer of 1832 Walt worked at

Worthington's printing establishment. He then went on in the fall to

work as compositor on the Long Island Star. In 1833 the

Whitman family moved back to the country while Walt stayed behind and

contributed pieces to the Mirror, one of Manhattan's best

papers (Parker 916). By the time Walt was sixteen he had become a

journeyman printer and a compositor in Manhattan (Parker 916).

Due to a disruption

in the

printing industry in 1835, Walt rejoined his family (Parker 916).

Whitman than went on to teach in various schools on Long Island

throughout 1836-1838. During this time Whitman also participated in

debating societies, worked briefly on a Long Island paper, and

started a paper of his own (Parker 916).

Whitman began the

series

"Sun-Down Papers from the Desk of a School Master" for the Long

Island Democrat in 1840. He also began campaigning for Van Buren

in the fall of the same year. Whitman began speaking at Democratic

rallies, and publishing stories in the Democratic Review

(Parker 917). In 1842 Whitman began editing for The Aurora and

The Tattler. He then returned to Brooklyn in 1845 and began

contributing to the Long Island Star.

In 1846 Whitman took

over as

editor for the Brooklyn Eagle. He was responsible for a

majority of the literary reviews featuring authors such as Carlyle,

Melville,

Emerson,

Goethe, and several others. Whitman was fired, however, from the

Eagle in 1848 for opposing the acquisition of more slave

territory (Parker 917). So on February 11, 1848 Walt and his favorite

brother Jeff left for New Orleans to become editors on the

Crescent. Whitman went back to New York in the summer of 1848

and began experimenting with poetry (Parker 917). He also served at

this time as delegate to the Buffalo Free-Soil convention.

In 1851 Whitman

began

building houses in Brooklyn. Now back with his family once again

Whitman would spend his days reading at libraries, taking strolls,

and writing in the room he shared with his brother (much to their

annoyance). He became a student of Egyptology and astronomy. Whitman

also began to annotate and argue in the margins of articles featured

in the British monthlies. He began to develop and formulate his ideas

on pantheism. By the end of 1854 Whitman had given up carpentry and

newspaper work for writing (Parker 917).

In July of 1855

Whitman's

first edition of Leaves of Grass went on sale. Soon after its

release Whitman's father died and he became responsible for his

mother and youngest brother Edward. Upon having received a copy of

Whitman's book, Emerson responded with a letter proclaiming Walt to

be at "the beginning of a great career." (Parker 918) After weeks of

few reviews Whitman "wrote a few himself to be published

anonymously." (Parker 918) Whitman also sent presentation copies

featuring Emerson's letter to writers such as Longfellow

(Parker 918). Soon after, Whitman would be visited in Brooklyn by

Emerson, Thoreau,

Bronson

Alcott, and

others.

After lecturing

locally for

a time, Whitman would go on to write Live Oak, with Moss. The

twelve poem collection proclaiming his love for another man, which

would later be revised and renamed Calamus, was hidden among a

cluster of counterbalancing poems along with Enfans d' Adam

(Children of Adam) in the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass

(Parker 919).

On December 14,

1862,

Whitman read that his brother George was among the list of wounded

soldiers on the war front in Virginia. He left immediately to be with

his brother and upon his return to Washington he began to visit

soldiers in the Brooklyn hospitals (Parker 920). This lead to a

series of war poems collected in Drum-Taps in 1865.

Whitman clerked for

several

years in the attorney general's office while continuing to rework

Leaves of Grass. In London 1868, a volume of Whitman's poetry

was published by William Michael Rosetti creating many English

admirers (Parker 921).

After a severe

stroke and

the death of his mother in 1873, Whitman moved to Camden, New Jersey

to live with his brother George. He would later die in Camden, after

publishing more editions of Leaves of Grass, on May 26, 1892.

"Of all the American

writers

of the nineteenth century, Whitman offers the most inspiring example

of fidelity to his art." (Parker 922) Though many viewed Whitman's

work as obscene, he refused to compromise himself or his work. He

died as he lived, a man of great compassion, perseverance, and

dedicated to his work.

Works Cited

Allen, Gay Wilson. The

New Walt Whitman Handbook. New York: New York University Press,

1975

Allen, Gay Wilson. Walt

Whitman as Man, Poet, and Legend. Carbondale: Southern Illinois

University Press, 1961

Bazalgette, Leon. Walt

Whitman the Man and His Work. Trans. Ellen Fitzgerald. New York:

Cooper Square Publishers Inc., 1970

Parker, Hershel. The

Norton Anthology of American Literature. NewYork: W.W. Norton

& Company, Inc., 1995

Study

Questions

1. Notice that

Whitman's

"Song of Myself" begins with "I" and ends with "you." To what extent

can the poem be understood as a transaction from an "I" (eye?) to a

"you"? Consider too the first activity of the "I" in this regard: he

loafs and observes a spear (why a single spear?) of summer grass. In

what sense is this observation typical of the movement leading from

"I" to "you"?

2. Whitman has often

been

accused of being egotistical. Discuss his use of "I" and its relation

to the country at large. Why does he appear egotistic? What is his

purpose?

3. What is Whitman's

view of

his physical self? Why does he stress it so much?

4. Discuss Whitman's

poetry

as a culmination point in the development of American identity. How

does Whitman contribute to the ongoing evolution of self-reliance? of

human freedom? of concepts of democracy?

MLA

Style

Citation of this Web Page:

Reuben,

Paul P. "Chapter 4: Early Nineteenth Century: Walt Whitman" PAL:

Perspectives in American Literature- A Research and Reference Guide.

WWW URL: http://www.paulreuben.website/pal/chap4/whitman.html (provide

page date or date of your login).

Top